The Aesthetic Compulsion

Reflections on aesthetics

The following article displays how I personally journal to work through a topic, here the concept of aesthetics, to gain an improved understanding on it. Hence the first section concerns only the concept of aesthetics itself, and later sections relate them to Stoicism using the practice of ethopoetic journaling.

Reflections on aesthetics

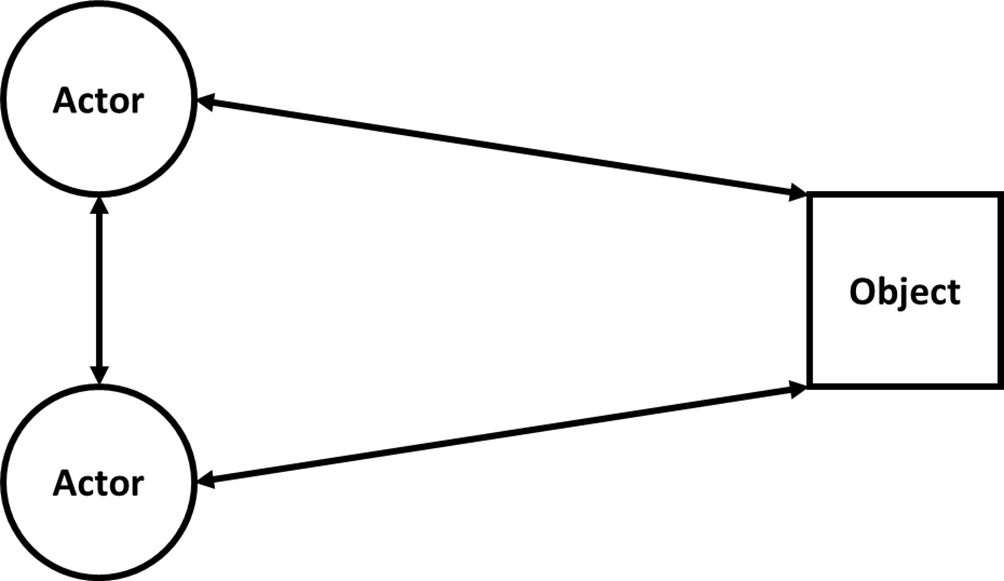

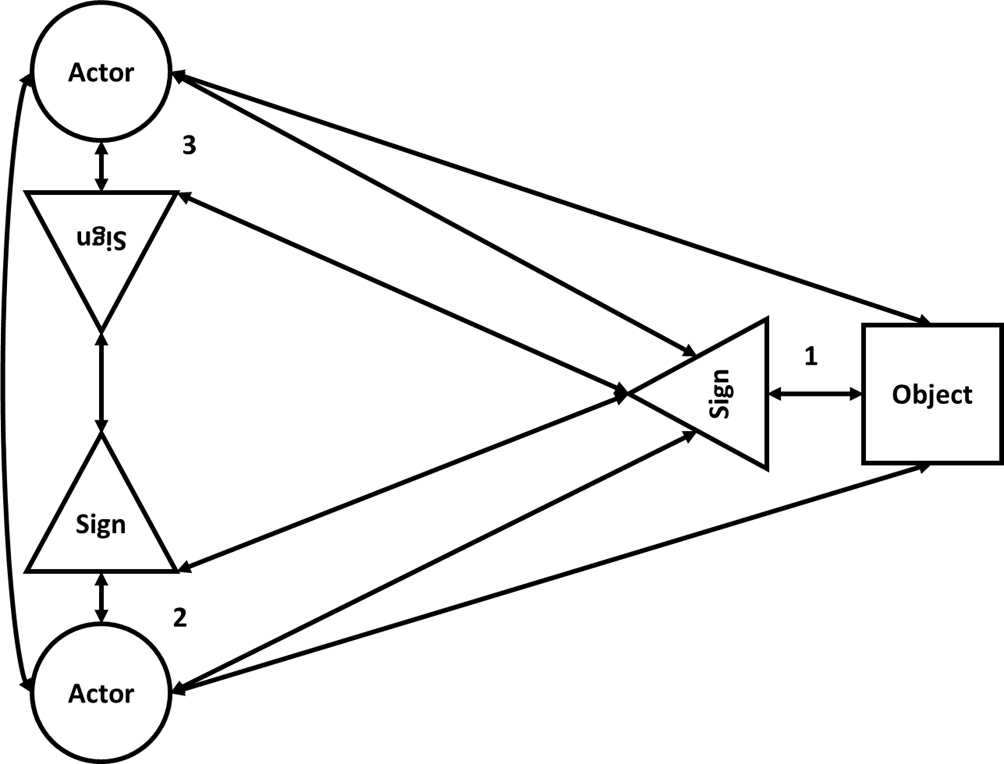

On the originary scene, the human is inaugurated when the object of the proto-human group’s appetite becomes the originary sign through issuance of the gesture of aborted appropriation, becoming the first instance of abstract language, and saving the group from their mimetic crisis. As theorized within Generative Anthropology, this was enabled by a fundamentally new mode of attentionality that we call “3rd order attentionality” where attention “flows” in all directions between social actors and object of attention.

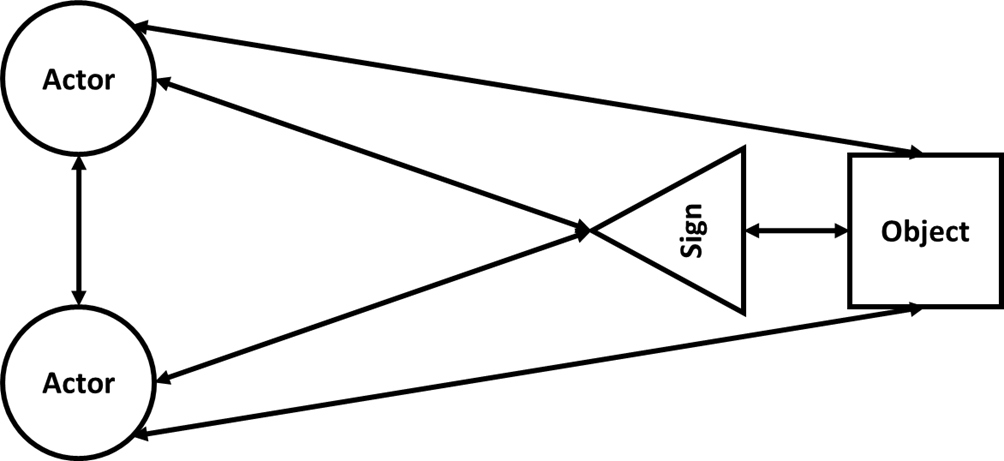

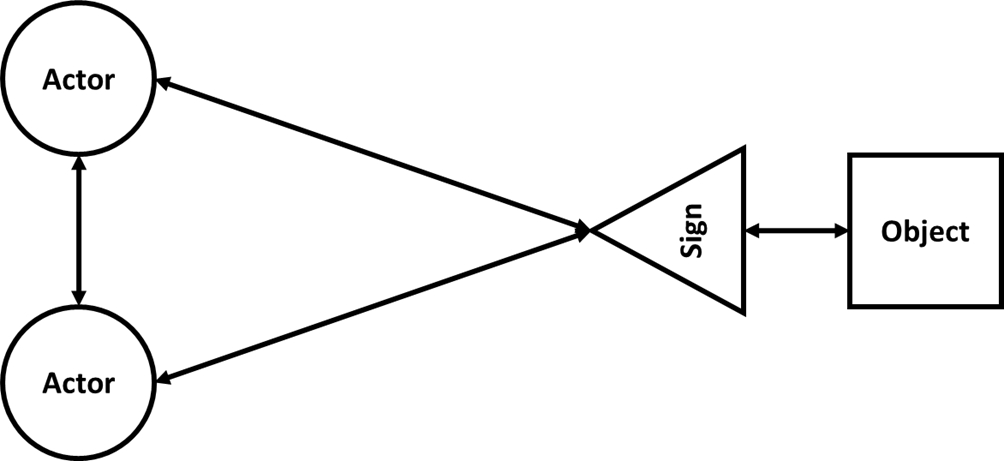

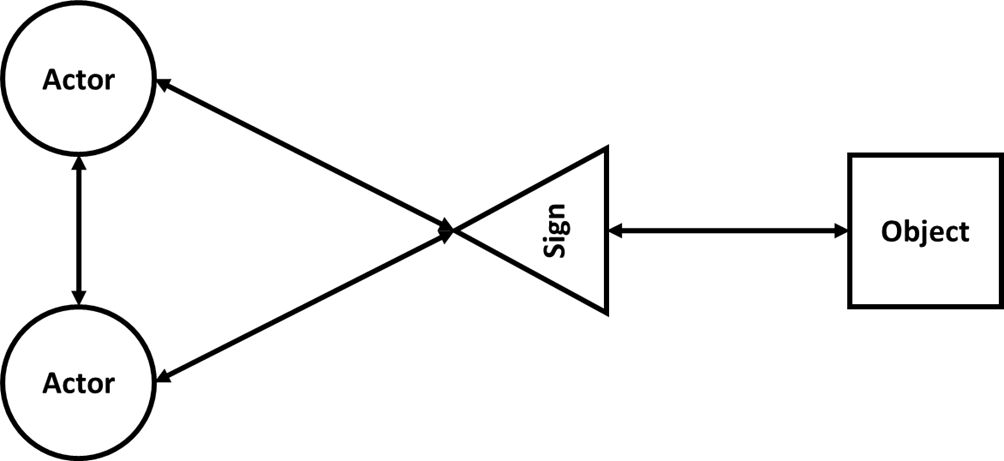

In his (extensive) writings on aesthetics, Eric Gans at its most basic outlines the aesthetics experience as being a relation between sign and object. As actors, we contemplate both the sign that represents the object of attention, as well as object itself. This is a paradoxical experience he remarks, because the significance of the object is conferred by the sign, but the sign is simultaneously only a representation of the object of attention. As Gans lays it out, this relation between the sign and object presents the object as ontologically prior to the sign, and thus guides its observers to contemplate the object alone; but in the absence of a sign, the object doesn’t carry any significance, and observers are thus returned to the sign once more. The sign designating the object within the wider symbolic order becomes an integral element of the object itself – I.e. how the object is represented by the sign frames the object in relation to all other signs within the symbolic order; how it should be viewed, treated, judged, and so on. Eric Gans goes on to point out that while objects can certainly be observed without a sign, they’re insignificant and don’t confer any reason to pay attention to them.

On the originary scene, the kill that the group is converging to appropriate for themselves – as individual members – poses the threat to the groups undoing by way of mimetic violence. When the object of appetite becomes represented by the originary sign, it becomes imbued by collective significance and meaning, convergent with the collective intentionality of the center. And in addition to attention oscillating between actors and objects on the scene, attention now also oscillates between actors, object, and the sign that represents the object.

The sign is imitated by all members on the originary scene, and Eric Gans asserts that what makes the actors want to imitate, and to continue imitating, the gesture of aborted appropriation – the originary sign – is that it is indeed a sign, and that it evokes its object without attempting to appropriate or take possession of it. The sentence may sound convoluted, but the members on the originary scene (and really any scene) has to be convinced and conclude that the sign evokes its object without attempting to seize it. The sign is an accessible representation to the inaccessible object, and, from my reading of Gans, it’s this oscillation between the sign and object, the recognized inviolability in lieu of imagined possession (or rather, the oscillation between possession and prohibition) that produces the aesthetic experience.

And the more “distance” there is between sign and object – i.e. the more prohibited its appropriation is – the greater the aesthetic experience is, i.e. the more beautiful it’ll appear to its observers.

Those who’ve read my book or previous article may be slightly confused – isn’t this just mimetic desire and resentment again? And yes, mimesis that converges on the same object is intensified into mimetic desire, mutually increasing one another’s desire to appropriate said object for themselves; and the ensuing mutual refrain from appropriating the object (out of fear from escalating mimetic violence) produces the resentment that goes with not being able to possess it. Hence the aesthetic experience is very closely related to the phenomena of the originary sentiments, but the aesthetic distinctly lies in the oscillation between the represented object through the sign, and the object itself. Specifically, Gans suggests that the resentment generated by precluded desire is dissolved or absorbed within the aesthetic relation: “In the aesthetic experience, the desire aroused by the object is continually relocated from the center to the sign-referent relationship. Real, worldly desire for the object is displaced into a universe of representation”. And he specifically points to new forms of resentment giving rise to new forms of aesthetics to defer them1. And here I want to take a moment to add a little of Dennis Bouvard’s writings as he puts it eloquently: “The desire for the object is magnified when the participant’s attention is directed toward it by the gesture of the other; the object then attended to directly is stripped of that desirability, when then has the participant return attention to the sign”.

Signs take hold, are imitated, and passed on, by actors because they’re significant, a significance the sign’s conferred by the aesthetic appreciation of it – i.e. it’s beauty. As Gans puts it, the originary sign didn’t just refer to its object; rather, it must’ve principally been judged to be beautiful – and he goes on to state that “it’s the aesthetic judgement that gives the human self a stake in signification”. Thus Eric Gans is seemingly in agreement with Friedrich Nietzsche that life, at its core, is aesthetic – and everything else is derived therefrom – as the famous line from The Birth of Tragedy goes: “it is only as an aesthetic phenomenon that existence and the world are eternally justified”.

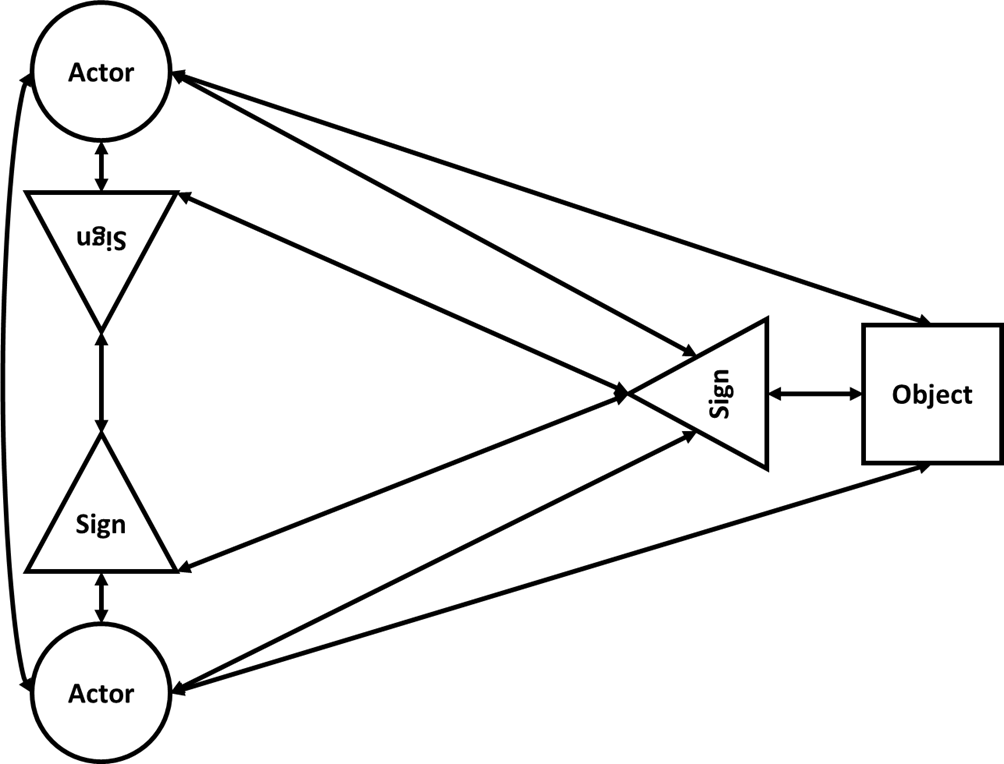

Eric Gans goes on to assert that the beauty of the sign lies in how it’s both “observed” and “performed”, and how it’s through one’s observation and imitation of others that one’s own performance of the sign is understood as an act of signification. He goes on to suggest that “the individual attends not only to that individual’s signifying act but to those of the other members of the community”; as I read it, we’re not only observing the object and it’s sign, and we’re not just observing the other social actors absent representation – i.e. a sign, because all representations are ultimately a sign . Supplementing with some of Dennis Bouvard’s writings, he likewise suggests so when he writes “Aesthetics is located on the originary scene, in the oscillation of the attention of the participants between the sign put forth by the other and the object”.

Thence, like the object and sign before, we’re additionally also observing the other actors as signs, as well as the actors in themselves – and therefore the same aesthetic effect is at work between actor as “object”, and actor as “sign” (including oneself). Bu not only the other actors, due to 3rd order attentionality, we’re also now observing ourselves and how we’re representing ourselves – i.e. as a sign – to the other actors and their signs, and in relation to the object and its sign. Consequently, there’s also an oscillation between the different signs on the scene (i.e. the sign of the central object of attention, the sign that represents oneself, and the signs that represent the other actors on the scene).

Accordingly, aesthetics still operates in a collective context, but it would necessarily have to given how humans are mimetic being which enables this whole oscillation to begin with – and Dennis Bouvard suggests it’s through the aesthetic that the intentions of the center is discerned through the attention of the other actors on the scene.

I think a clear example of how the above works in practice would be something everyone is familiar with: How to dress.

When one picks out an outfit for an occasion or other, the first thing one would consider is the occasion itself; is it for work? A gala? A bar? A festivity? These are examples of objects and their signs, which set the whole scene; i.e. we’re not likely to consider a formal gala to have the same aesthetic reflection as a disco – which already gets us thinking about ourselves and ourselves as signs, in relation to the object and its sign.

Once we’ve begun measuring ourselves and our sign against the object and its sign, the next step is inevitably going to be a consideration of how the other actors are going to measure themselves and their sign up against the object and its sign – i.e. how they’re going to be dressing. Again, now we’re measuring ourselves and ourselves as sign, up against the other actors on the scene, and the other actors as signs on the scene, in relation to the object and the object as sign.

This’ll then end up determining how oneself will end up dressing, i.e. a measure of oneself and one’s sign, against the others and their sign (and again, the object and its sign), and which aesthetic reflection one wants to convey in relation to everything else on the scene. Therefore, even when one’s trying to pick out clothes to wear alone, it’s still collectively determined by the aesthetic that those objects and signs carry with them.

I want to note that the above works both when one’s acquiescing or transgressing to the aesthetic reflection put forward by the object and other actors on the scene. As a hypothetical example, should one be of the Cynic persuasion, one would still need to go through the above to ascertain the kind of aesthetic reflection that’ll have the maximally transgressive effect; whether one was parodying, satirizing, or totally countersignaling the aesthetics of the scene. Even in the event one is deliberately seeking transgression, one is still ultimately bound by the the aesthetic one is transgressing against – at least if one seeks to achieve the intended effect – and only by doing so may one be succeed in mimetically impressing upon the sign and its object, as well as the other actors on the scene and their signs, so as to change and transfigure their meaning and aesthetic (for example, at a social gathering where the other actors are wearing expensive furs, one might attend with something that displays the animal suffering and cruelty of the fur industry, thus completely reframing the social scene). And obviously the possibility of a social faux pas is still retained, where one is unfamiliar with the signs and mimesis they elicit and thus completely misjudge the aesthetic one should reflect.

To put it more loosely, aesthetics is a sort of double-sided reflection of how we “want” to view or perceive ourselves and the world: How things ought to be. As those who’ve read my book or even previous articles will know, virtue is located at the unique intersection between ethics and morality on the human scene; ethics being the encoded moral agreed upon symmetries within the scenic stack; and morality being the symmetry between the actors on the specific scene. But the thing that compels what should be morally agreed upon in the first place is aesthetics and thus lays the foundation how the scenic stack is going to develop, and what’ll end be considered virtuous in the first place. This doesn’t immediately upend the model I’ve hitherto presented, but informs how it originates. Hence the foundation of morality, ethics, and thus virtue, lies in aesthetics.

Implications on Stoic theory

Obtaining a greater understanding of aesthetics is ostensibly a worthwhile pursuit for the Stoic scholar, as it has implications for the principal pursuit of Stoicism: Virtue2. Because virtue is constituted by ethics and morality, which are initially compelled by aesthetics, it’d be prudent for Stoics who seeks to change, or advance, a particular moral modality to reflect on its originary aesthetic compulsion and how it may – if you want to advance it, how’s it going to be the most authentically and compellingly advanced? If you’re going to war against a particular aesthetic, how are you going to reflect it the most vulgarly3?

As a practical example, consider an aesthetic outlook like veganism. The aesthetic compulsion of an avowed vegan will typically involve some form of compulsion against what they consider the aesthetic grotesqueness of slaughtering animals for human consumption and benefice – and a compulsion for protecting and living in harmony with wildlife. To advance their cause, the insistent vegan would likely do a mix of making their aesthetic compelling by e.g. focusing on supplementary aesthetics compulsions like health, sustainability, and, well, cute animals; and conversely attack the prevailing aesthetic that enables the slaughtering of animals by reflecting the vulgar aspects that assaulted aesthetic permits. This could e.g. be through showing the conditions that farmed animals live under, the slaughter process itself, equivalating the family of slaughtered animals with a human family, etc. as well as again bringing in supplementary aesthetic vulgarities like unhealthiness and unsustainability, as well as e.g. things like the spread of diseases from animals to humans.

The above thought experiment showcases a few things. Firstly, it showcases that how signs and aesthetics are interrelated within the symbolic order. Because aesthetics (particularly in the complex societies of the present) and signs are connected and intersecting with other signs and aesthetics – which can be called upon to supplement one’s aesthetic. E.g. we had an aesthetic compulsion that resulted in the moral modality of veganism; to supplement it, a connection can be drawn to a more dominant – and thus more widely accepted – aesthetic like that of “health” – and if the connection is successfully established, it can be called upon and lend its own credibility and acceptance to the less conventional aesthetic. And thus, by establishing relations within the symbolic order, the aesthetic will gradually establish its own place, legitimacy, and convention within the symbolic order. Conversely, by associating a rivaling aesthetic with aesthetic and symbolic relations that are considered repulsive, it’ll gradually begin being considered repulsive on its own. Hence there’s a whole web of “good” and “bad” relations which are, in principle, as arbitrary as language itself, but must be navigated nonetheless.

Secondly, it showcases what’s typically considered moral conundrums as being miscategorized – they’re actually aesthetic quarrels. Veganism is one example, but the examples are innumerous: Abortion, guns, ecological sustainability, sexuality, what’s appropriate in public, what’s accepted in private, etc. are all examples of issues that are firstly aesthetic in nature. Because morality is the about the established symmetry on the given scene, and ethics are the agreed upon scenic symmetries within the scenic stack – but morality only concerns social actors who can share a scene, i.e. language users, i.e. humans4. E.g. because animals cannot sign and learn abstract language, they cannot share a scene with humans, and thus whatever concerns them falls entirely on humans – meaning aesthetics. How should they be treated? How should we let them live? What do we use them for, if anything? These are all aesthetic reflections (or rather, reflected on by the given aesthetic), and from there humans as social actors agree upon something on a scene, whereupon it then concerns morality and down the line is encoded into ethics.

This is likewise important for the Stoic to understand in their pursuit of virtue. Particularly when they’re being warned that a given moral modality, based on a specific aesthetic, is the only way to truly be virtuous5 – and equally important when they’re being admonished for holding to a given aesthetic. To reiterate, a given aesthetics compels the formation of certain moral symmetries that reflect the aesthetic, and thus a certain ethics within the scenic stack that forms on top of the given aesthetic; therefore, if the Stoic is committed to advancing that scenic stack, that line of succession, adopting ethics, moral symmetries, and ultimately aesthetic, may be in violation of the ones hitherto served, and thus vicious to the contextual virtue. And to be clear, all virtue is ultimately contextual to the given scenic stack – in the originary conception of Stoicism, there doesn’t exist a metaphysically ideal form of virtue, separate from the human and mimesis.

Though a word of caution may also be in order. Because aesthetics lies at the very foundation that compels humans as actors6 we’re dealing with things people truly find significant. I.e. these are things that people are willing to go to war over, to kill and die for. Hence I must urge Stoics to refrain from being lackadaisical when operating on this level, particularly when they pursue transgression – even if they’ve deemed it virtuous. When not executed right, one may just come across as mocking, or not really understanding the aesthetic they’re targeting at all, and thus just come across as an immature bad-faith actor. And given the role aesthetics plays in absorbing and assuaging resentment, one’s interjection may well spill over to violence if one’s efforts manages to disrupt a given aesthetic relation enough that it can’t absorb the resentment adequately anymore (even temporarily) – why the emphasis on doing so with a substituting aesthetic at hand (if for nothing else as a backup).

The aesthetics of Crates

In my previous article I mused on how Crates of Thebes may supply an alternative model for the Stoic to imitate; along with situating how some topics closely related to Crates – but not conventionally related to Stoicism – ought to be regarded and treated from a Stoic point of view. I realize now that what I was actually grappling with was an alternative aesthetic reflection on what it means to be a Stoic. When people think of a stereotypical Stoic, they think of someone somber and serious, rational and unfeeling – learned Stoics may object, but I think few would dispute that’s how Stoicism is aesthetically presented and reflected most of the time, even by its adherents. A Stoic who imitates Crates could (and likely would necessarily have to) put a different aesthetic spin on what it means to be a Stoic.

A classical Stoic approach could for example be, when in the company of others, to exclusively paramimetically counteract the mimesis one is met with, to insure one’s cylinder doesn’t move without being in full control; instead, the sort of alternative Stoic approach I’m inquiring into may lead with the sort mimesis that he wants the others imitate and reflect back on himself – i.e. when he’s just joining the group, or it’s forming, he’s already reasoned out which type of collective behavior would be the most effective or virtuous for the task or occasion at hand, and can thus do his best to exhibit the sort of mimesis that’d encourage the desired behavior on a collective level (and continue to do so if some prove resistant, especially in ways that may derail the group).

Obviously, that’s just a thought up example on how the two aesthetics may end up informing action differently even in the service of the ostensibly same goal, and such a subinquiry would be better off pursued in a separate article. Bottom of the line is that what matters to Stoicism, to adhering to the ethos, is that one pursues and acts in the service of virtue (which it classically does recognize and allow for too). In my book I remark on the aesthetic difference between Diogenes of Sinope (the founder of Cynicism) and Crates of Thebes when exploring the Cynic pedagogy I nest within the Originary Stoicism; and given that Friedrich Nietzsche has already been brought up, his aesthetic categories seem applicable. In my book I label Stoicism “Right Hand” and the nested Cynic pedagogy a “Left Hand”7 version of Stoicism that the Stoic can employ when the Right Hand suffices no longer – though as I also maintain the my book, Stoicism will first and foremost be a Right Hand ethos.

However what’s being explored here in this inquiry (along with my previous article) are both instances of Stoicism, albeit with differing aesthetic reflections. In this case, Nietzsche’s aesthetic categories of the Apollonian versus the Dionysian may be more applicable. The classical aesthetic reflection of Stoicism is Apollonian in drive, elevating reason, logic, and order, through which Stoicism (especially “stoicism” with a lowercase s) derives such a heavy emphasis on self-control and detached distancing oneself from others, and avoiding passions. On the other hand, a Stoicism modeled on Crates of Thebes with a Dionysian drive would likely elevate instinct, intuition, and inspiration, as well as spontaneity and probably even emotions8; with a strong emphasis on participation, meeting others where they are and then (mimetically) transfiguring them – as Crates himself is accredited of doing, curing the Athenian citizens of (mimetic) afflictions, earning him the status of a household deity. The learned Stoic may object that “true” Stoicism doesn’t dictate the former, however in practice that’s what aesthetic reflection of the Apollonian drive encourages. And to reiterate, this would still be within the Stoic primary mode, and not within the nested Cynic pedagogy.

A clear example of the difference is one that I’ll admittedly eclectically steal from modern philosopher Byung-Chul Han, is the difference between modern James Bond films (i.e. the ones with Daniel Craig) and the older movies. In the classical films, James Bond was a bit of a playboy, not shying away from party and play, and occasionally getting in a pickle because he’d fancied the titular Bond-girl, overall being a little bit of a loose cannon even for his employers. Take a look at the ending of The Man with the Golden Gun - James Bond puts his boss on hold to enjoy the company of said Bond-girl. Conversely, in the modern movies James Bond is much more serious and focused, cold and calculating, sometimes being described as a small-s stoic. Take a look at the ending of Skyfall – James Bond is unphased by the titular Bond-girl, and rather immediately takes on his new assignment “with pleasure”. Hence the classical James Bond could be said to have a Dionysian drive, and the modern an Apollonian drive.

Final thoughts

Where the categories of morality, ethics, and virtue emerged in antiquity, aesthetics is a later category that was first distinctly categorized by German philosopher Alexander Baumgarten. Hence the ancient Greeks didn’t have it available as a distinct object of inquiry, as a sign on the scene of representation – and when you don’t have a sign that represents something, it’s difficult to even conceptualize, let alone analyze and treat. To be sure, the ancients did have thoughts on matters that we’d today categorize as aesthetics, but it wasn’t independent of, or mixed into, other categories and concepts. Which with high probability explains why their attention was so focused on morality, ethics, and virtue (literally amounting to the distinct philosophical category of “virtue ethics”), and why they didn’t give this aspect of philosophy emphasis – why we ought to do so now.

However (and that’s a big however) if we go a bit beyond the purview of the Stoics, to other Greeks such as Aristotle and Plato, we find that they do make a connection between “the beautiful” and virtue. They posited that virtue being true human excellence, has a visible appearance – which they called “the beautifully done”. Aristotle’s entire ethical framework essentially centers around the concept of “the beautiful” (to kalon) and is the definitive end to virtue and human action. Therefore the importance of what we now call “aesthetics” can’t be understated, and that virtuous actions, actions that are truly good and excellent, will appear as beautiful. That is to say, when they authentically reflect the underlying aesthetic foundation, allowing the significance that the aesthetic carries with it to truly shine through.

And as an addendum, throughout this article I’ve been attempting to associate different adjectives – e.g. “warm” and “cold” – to different aesthetic reflections, so that it’s easier to comprehend how different aesthetics shake out differently throughout the higher orders of human life. The reason it sounds so odd is, as Eric Gans often emphasizes, that aesthetics is an experience, something that’s only really ostensively perceptible. It is not a declarative proposition, and hence when trying to unfold what one aesthetic might be experienced like in contrast to another, we’ll be forced to use these comparative concepts that proximally “measures” the difference. However, aesthetics is always contextually bound, just like virtue is, and thus what the same aesthetic reflects on a given scene might differ considerably from what it reflects on another. Hence when two or more aesthetics are at odds at one another, the best “argument” one can put forth is to gesture toward there being an aesthetic difference, and then to assist others in experiencing one’s favored aesthetic as oneself experiences it, to compel them to shift their aesthetic inclination – and conversely, when one can’t seem to fathom why someone would to hold their aesthetic inclination, try to experience it as they experience it.

And just because one’s experienced what’s beautiful in a given aesthetic obviously doesn’t mean one must necessarily adopt it; particularly in the case where one’s also experienced what’s ugly in another aesthetic – which will typically mean how the unfolding of the aesthetic expression impedes on the expression of other aesthetics and their beauty, trampling on them and destroying their beauty in the process. Taking the prior example, there may be a certain beauty in halting the exploitation of animals – yet for that beauty to be realized it must essentially displace the beauty there is in e.g. the bond between man and animal working together, or tradition, or something third. Hence comprehending why things are the way they are, why people do what they do, through experiencing what aesthetically compels a given facet of human culture for being the way it is, is deeply beneficial to acting in the service of virtue. That goes for both acting to advance a given cause, or to change a facet of the nomos to something else.

Eric Gans identifies five sets of overarching aesthetics throughout (known) human history, which each represents genuinely new ethical systems following with it.

And hence, by extension, achieving eudaimonia.

It goes without saying that having a compelling alternative at hand would be beneficial.

No animal has of yet been demonstrated to be capable of abstract language. So for the time being, the only plausibility for other beings is extraterrestrial life.

I located this article after-the-fact, when searching for whether others had covered the topic.

Other than what in Generative Anthropology is called “the sacred” which Gans claims that aesthetic is a secularized separation from, but given Stoicism is an ethos this isn’t proximally relevant.

Categories inspired from the mystic tradition.

In the sense the term is understood in my book, where emotions are mimetically elongated feelings, in the same sense that (mimetic) desire is mimetically elongated appetites.