The Highest Good

Why Zeno was right

When faced with the question on how to attain what the ancient Hellenes called “eudaimonia”, the founder of Stoicism Zeno surmised that the only thing that could ever have any relevance was virtue; everything else being indifferent. This was in contrast to previous major philosopher whom, while also finding virtue important, didn’t think virtue was sufficient by itself to achieve eudaimonia. This went against the teachings of e.g. Aristotle, who believed that a certain degree of pleasure was also necessary in order to achieve eudaimonia.

To achieve eudaimonia, he formulated what I call the “founding idiom” of Stoicism. It’s the most minimal expression of Stoicism possible, yet captures the entire ethos into one elegant formulation: To live consistently with nature. For the uninitiated, I’d recommend the article I wrote for the newsletter Stoicism Today that lays out the idiom in its entirety: https://modernstoicism.com/what-stoicism-is-an-anthropocentric-account/

Thence to the Stoics, virtue became the highest – uncontested – good. The founding idiom guided the philosophical inquiry, focusing on how virtue is best achieved most regularly in ways that are actually practically possible. They set aside everything that ultimately weren’t relevant to the strive for virtue, developing theories, techniques, and advice that endure to this day, and are enjoyed by an increasing following of practitioners. The following article will seek to ascertain how the brilliant elegance of Zeno’s, and Stoicism’s, elevation of virtue was able to achieve such lasting efficacy.

Examining Potential Highest Goods

Let’s begin the examination by contrasting virtue to other potential candidates for highest good, and see if it reveals something about the nature of virtue. This’ll be done by considering the various concepts or values in isolation, irrespective of their origin, to observe the limitations inherent to them when elevated to a highest good. A highest good, meaning that it’s considered the all-encompassing thing that we’re looking to achieve in all aspects, guiding our actions towards those ends. And what could be more befitting than contrasting it to the highest good of its main rival school, Epicureanism: Pleasure.

Pleasure

A person intent on maximizing pleasure wherever they can, letting their every action bear in that direction, will have to face a choice, as ancient Cyreanics and Epicureans had to content with: On what time horizon? I.e. does one maximize pleasure in the moment, or the long run? Or somewhere in between?

Shortsighted hedonism should be plain to most people what the limitations are: What if the immediate gratification is closely followed by pain or discomfort? For example, feeling a little hungry, so you snatch food from someone else’s hand or plate – it might quickly satiate your appetite, but is liable to get you into mental, if not physical, anguish. For an individual, this sort of guiding principle will quickly see oneself in trouble; as community or society, this sort of value will spell catastrophe, swiftly consuming all social and economic capital, descending into violence and chaos.

At the other end we have farsighted hedonism, where one (as the Epicureans attempted) try to plan one’s life and maximize pleasure over the course of a whole lifetime, trading short-term pain and hardship for setting oneself up for more lasting pleasures one can sustainably indulge within the expected time frame. Ostensibly, this could work on an individual level, as one sets oneself up in the “beginning”, and then enjoy the fruits “later”.

The first issue emerges, however, when having to determine time horizon. How long does one expect to live? Nothing is certain, so one may work all one’s life and then plan to enjoy one’s retirement to the fullest, only to then die before retirement – thus never getting to actually experience the pleasure one had in waiting – or, alternatively, one may become incapacitated or suffer from a diseases like Alzheimer or dementia, making oneself unable to take part in the pleasures that were planned. Or one may just live past what was expected, to suddenly find oneself in the most hardship when one is the least capable.

Secondly, how much pleasure does one wish to enjoy? Does one get maximum pleasure from just being relieved of pain (as the Epicureans concluded) or does one actively need to experience pleasure? The issues is related to the previous one, as one has to ascertain how much pain and adversity one needs to trade to experience the desired comforts. And how does one even determine what will provide greater pleasure over something else?

With modern understanding of the human psyche, we now also know of the phenomenon named “hedonic adaptation”, where a pleasure, comfort, or something else desired becomes devalued through normalization after it’s acquisition. E.g. after obtaining the new phone that everyone’s been so hyped over, it gradually becomes taken for granted, and thus the pleasure imparted gradually decreases. Hence if one’s guided by the continuous attainment of pleasure, one will in equal manner have to continuously obtain new objects, experiences, and stimuli to keep it up – something that over time will become a job in itself, and seems almost certain to lead to more anguish than one may anticipate.

And that’s only on the individual level – as guiding values for a community or society, the issues become exacerbated. For example, on the issue of timeline, how does society come to agree when it’s time to stop toiling and start savoring. Hard limits can be put in place, say, retirement age is at X years old, to when individuals can start enjoying themselves – however that’s just averages, and leaves a certain percentile of the population to never experience pleasure, or at least not maximize it. Alternatively, a society may decide to build itself up to a certain level, and when that’s reached, everyone gets to enjoy themselves. However what if that requires numerous generations? Do untold amount of generations just toil away, with little pleasure in their lives, until some generation down the line fulfills what was one promised, and from there the generations on just delight themselves in perpetuity? To not even speak of the hedonic adaptation that’d set in, how do we know when is the right time to stop? Perhaps just toiling a little more will develop hitherto untold forms of pleasures that couldn’t even have been conceived of in the past – e.g. if our civilization had just stopped advancing 100 years ago, what of the pleasures and comforts we possess today that couldn’t even have been imagined then?

Obviously this specific debate goes all the way back to antiquity, and this is not supposed to just retread the same ground – only make clear that there are numerous limitations to pleasure as a highest good (which I hope the keen reader found compelling) that prevents it from being a stable and viable highest good. However let’s continue by examining some values that are more contemporary, and observe how they fare by being elevated as the highest value.

Freedom

Freedom has become a much vaunted value particularly since the enlightenment took off, and has gradually expanded into many areas of society – freedom of speech, freedom of association, freedom of choice, freedom of expression, freedom of movement, freedom of information, freedom of religion, to mention a few. What would the implications of dedicating all ones action toward such an end be?

The first issue encountered with striving for unlimited freedom is that one may engage in harmful and destructive actions, which will quickly yield unproductive results. Because if one is free to engage in e.g. violent acts, then one will inevitably find oneself at the receiving end of reciprocally violent acts, resulting in ones incarceration, incapacitation, or demise at worst. Hence to obtain performative results we quickly find we actually have to limit our range of free actions that we can engage in.

Therefore, proponents of various strains of liberalism have had to resort to various principles and precepts in order to guide freedom toward productive ends. The most famous one, and as the extension of the issue raised above, would be the “Harm Principle” of John Stuart Mill who reasoned that the only legitimate injunction to a man’s freedom was in preventing him from harming others, a notion which is echoed numerous proponents of liberalism in the early enlightenment era. This is supposed to ensure that only freedom that is cooperative is allowed, by preventing violent acts like murder or assault, thus ensuring a form of freedom that’s even worth having.

Another issue arises however: What’s the threshold of what’s considered harm? For example, is one harmed by people cursing your name? Is spreading misinformation meant to hurt someone’s reputation considered harm? And salient to liberalism as an ideology, could competition in the free market be considered a form of harm? It’s plausible to harm in numerous ways, or to interpret innumerous actions to be potentially harmful. Which do we permit and which do we regulate? For historical examples of such laws, the 1891 “Slander of women act” in Great Britain, representing a woman as unchaste or adulterous could be taken to court, and she needn’t even prove that any harm had come off it. For a contemporary example, some US states consider it injurious to misgender another person; on the flip side, some US states now restrict the usage of pronouns in public institutions.

I hope it’s become clear already that as a highest good, freedom is a non-starter and has to be checked in innumerous ways to become functional – these checks implying there’s actually another even higher good in play, which are placing the constraints on freedom. However I want add a some more thoughts to the issues related to freedom. Because we’re always acting in some social context or other, which in practice puts a limit to our freedom, but simultaneously opens up potentials – the most fundamental being that of language itself, as we aren’t in charge of what things mean, but language simultaneously contains the potential for the kind of cooperation it enables to be able to transmit meaning and share a common foundation of meaning. At its extreme, freedom would mean being rid of any and all social relations and social obligations, rendering any kind of social order impossible (and the concept itself meaningless). At best, freedom refers to a space within which one has autonomy to decide and act, but freedom as a rebellion against disciplinary spaces and scenes is destructive and counterproductive (literally undoing productivity it could plausibly yield).1

Peace

Another value that may be interesting to examine as a highest good is that of “peace”. The idea of pacifism has gained much ground after the world wars, but has also seen a contraction after the invasion of Ukraine. Yet again we ask ourselves the question what were to happen, if it was elevated to the highest good as a value.

And as the invasion of Ukraine poignantly demonstrated, pursuing peace at all costs leaves oneself vulnerable to those who don’t have any scruples with employing violence. At its most extreme, it could entail one’s own subjugation or enslavement, preemptively surrendering oneself as one refuses to push back in the name of preserving the peace. And historically we find that eras of relatively enduring peace, like the Pax Romana of antiquity, or the Pax Americana today, are only backed up with vast armies – i.e. vast potential for violence. Hence peace only becomes viable when meaningfully backed up by the threat of force, the capability of imposing costs on potential aggressors – and therefore doesn’t work well as a highest good.

Even at a smaller scale it becomes an issue, as one may not confront people that need to be confronted (perhaps some person is harassing oneself or others), leaving an opening for behaving as unethically or immorally as they please. If one is to have a sustainable nomos at all, a viable succession, the peace will occasionally need to be broken and violators confronted and handled. It should be readily apparent the issues possessed by peace as a highest good, and therefore it’d be superfluous to consider the matter more.

Examining Virtue

As studied Stoics will know, and as mentioned in the beginning, Zeno surmised that in order to achieve eudaimonia, one must strive towards being virtuous at all times, with the notion of the “sage” being someone who’s successfully achieved the wisdom and cultivated his character to always act rightly. Directly translated, eudaimonia means “good spirits” but is interpreted as something like “flourishing”, “fulfillment”, “contentment”, or, particularly popular today, “happiness”. I personally hold to “flourishing” being the proper understanding of the term.

When pursuing virtue as the highest good, one seeks to always act in right reason, and always does the right thing given the social context. To the Stoics, there was always an appropriate action to be taken, and it was up to the individual Stoic to ascertain what that might be. Additionally, what might be appropriate for one Stoic isn’t necessarily appropriate for another – e.g. if there are two Stoics on the same social scene, where one is very learned and experienced with the matter at hand, and the other is a newcomer, the appropriate virtuous action for the experienced would likely to be to give his council, while the appropriate virtuous action for the inexperienced would likely be to observe and learn.

Now the first objection that could be given to virtue as a highest good is that it could be practically anything – how is one supposed to know what to do? Ostensibly it could read like it’s an empty concept, devoid of any content or direction, something one can just claim one is being. The ancient Stoics developed the concept of the “cardinal virtues” as a guide figuring out what the virtuous path is in the given situation. In their view, all four cardinal virtues had to be present and balance each other out in order for the action to be virtuous:

Courage

Justice

Temperance

Wisdom

For example, should one act with justice, temperance, and wisdom, but without courage, then one’s action was liable to be cowardly – and thus not virtuous. Now those who have a pernickety Socrates hidden within them might go on and ask what’s meant by these concepts – essentially just moving the issue one step back. However this formula seems to have served Stoics well enough over the centuries, and I think the next objection is more valid: Are these really the only ones? What about kindness, ambition, and honor? What about freedom and peace? Is there virtue to be found in e.g. violence?

The Coordinate of Virtue

Anyone who’s read my book will know that I use the theories and concepts of Generative Anthropology to analyze Stoicism through. Relevant to this discussion, I identify how virtue manifests on the human scene, with some very interesting results and implications in my opinion. Faced with the first objection to virtue as a highest good, I’d give a different answer to the ancient Stoics.

Because one interpretation of what the Stoics (and other philosophies) were attempting to do with the cardinal virtues was to impart some principles that when followed, would lead the practitioner to the “coordinate” of virtue on the human scene. In my book I took a different approach, yet still informed by Stoicism’s understanding of virtue: Because the Stoics considered virtue to be the highest ethical good and sole moral good. They didn’t distinguish between virtue and morality, as they were one and the same thing, but I supplement Stoicism with Generative Anthropology’s understanding of the concepts.

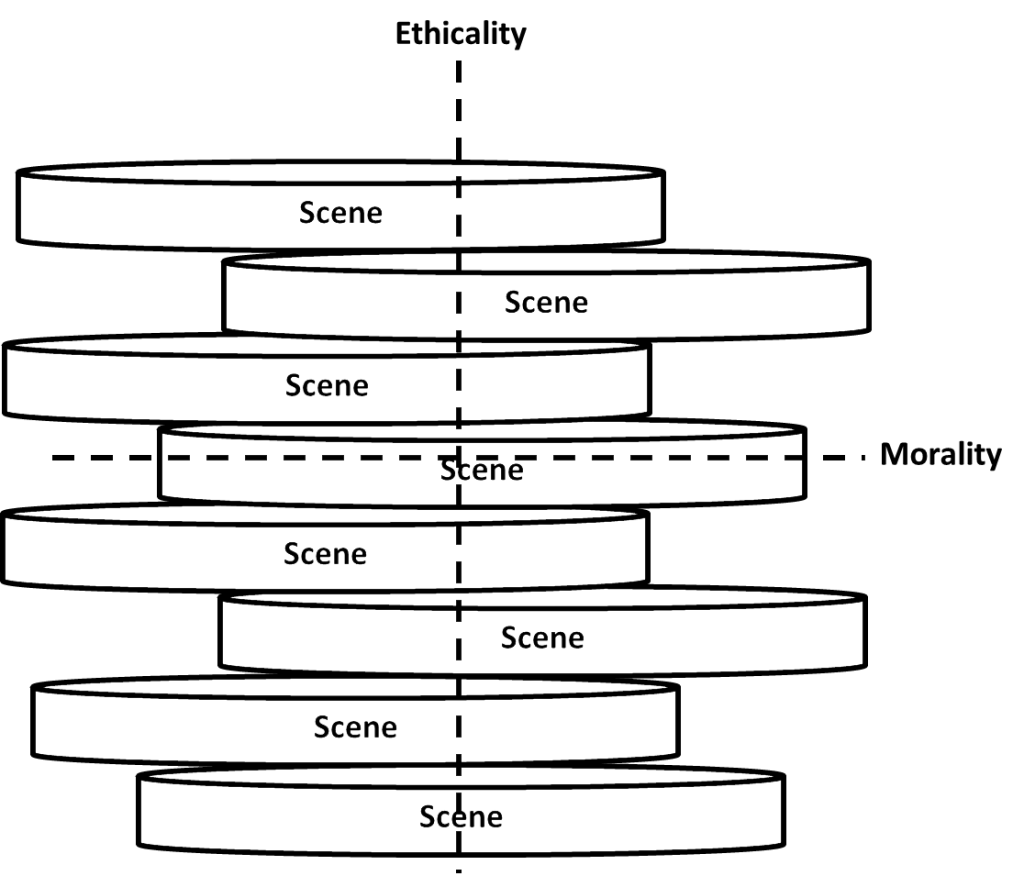

When it comes to ethics, ancient Stoicism and modern Generative Anthropology has a nearly identical understanding, which is “how to behave properly” – Generative Anthropology just modifies it slightly so it’s narrowed down to being particular to a given disciplinary space (I consider it an advantage to retain that nuance). Since there’s no separate Stoic understanding of morality, Generative Anthropology’s understanding of morality is of enforcing scenic symmetry between all participants on the given human scene (a separation and understanding I also consider advantageous).

With these understandings, we just need to locate virtue (something that wasn’t treated in Generative Anthropology’s literature beforehand). And what we find is that Stoicism actually provides us the coordinate on the human scene from it’s understanding of virtue as the ethically highest good and morally only good: Where ethics and morals intersect. I.e. virtue is when one acting ethically in accord with the established nomos one’s presently inhabiting, and morally in accord with the symmetry on the particular social scene one is acting within at that given moment.

For those who haven’t read my book, scenes can be stacked upon one another, and these stacks are what creates the nomos we’re in. A stack has one singular ethic that makes stacking of the scenes possible – that is, all the ways we have to behave, including what’s not allowed, to allow the scenes to stack and not “topple”. For example, to have free market capitalism there must necessarily be an ethic of respecting “property rights”. Contrary, each individual scene in the stack has it’s own moral symmetry.

Consequently, in order to be virtuous, one must understand the ethics of the stack the scene one is acting within, as well as the scene itself, to insure one acts right at the intersection where ethics and morality converge. Note that this understanding of virtue transcends local understandings and definitions; i.e. this isn’t just Stoic virtue, and to Aristotelians and other philosophies it’s something different. By locating virtue on the human scene, we can finally move beyond local declarative definitions and ostensively point to something that must be globally in common for all (one of the reasons I’m really impressed with Generative Anthropology, as it allows unprecedentedly clean demarcations and performative understandings).

Just to give some examples of immorality and unethicality: It’s plausible to be immoral while still ethical on a given scene, when one is doing something that the nomos of the stack doesn’t have anything codified on that behavior, but acting against interest of the moral symmetry on the social scene. And it’s plausible to morally right on a social scene but ethically wrong, when the scene violates the nomos of the stack – e.g. with the example of property rights earlier, if one finds oneself in a group of thieves, stealing violates the ethics of nomos (respecting other people’s property rights), but as long one acts honorably within the group (e.g. split the dividends of their unethical behavior equally) then one is morally in the clear, yet not virtuous.

The Perennial Good

Armed with an anthropocentric understanding of virtue, we can now address the first objection – or rather, sidestep it. Because it’s not technically false that virtue could in theory be anything, as varied as every scene and scenic stack – it really depends on the social context. However that doesn’t make the concept meaningless, far from it. Knowing that virtue isn’t any one thing, but rather a position or coordinate on the human scene means that we avoid crystallized dogma as to what is and is not good, while still retaining that there’s always something good that can be done in any given situation. I.e. the virtuous thing to do could be to give people on a scene the freedom to bring something of their own design to the center; other times the virtuous thing to do might be to limit and guide them (e.g. as a teacher in a classroom). Or the virtuous thing to do might be to make peace in one situation, but in another it might be to engage in conflict.

And when it comes to the cardinal virtues, we don’t just avoid Socratic pernickety, but recognizes the virtue plausible in all things. There’s a virtue in kindness, ambition, and honor; there’s virtue in freedom and peace; there’s even virtue possible in violence. There’s more paths to virtue, theoretically plausible in all things in the right social context – just as they can be vicious in the wrong social context. Conversely, notions that we commonly consider virtuous may in certain situations be vicious to engage in; e.g. if someone is going to murder another person, and you know where the other person is, it might not be virtuous to honestly report their whereabouts to the potential murderer.

It even gets ahead of another general criticism of virtue ethics, in that what’s virtuous may vary across cultures. And yes that is completely true, even within a culture it varies – within every scenic stack and every individual scene. Obviously in one culture that share scenes together, what’s virtuous will be more similar as they’ll share at least part of their ethical foundation. E.g. in the earlier example of free market capitalism, business built on that shared (stack of) scene(s) will share an ethical foundation of respect for property right; however from there, they’ll be separated stacks which generate divergent ethics, and thus nomos, within them, diverging what might be virtuous.

As a highest good, virtue is flexible because it holds the potential to be theoretically anything, yet persistent because it’s always exists as a plausibility on any given social scene (even if it means e.g. dissolving unethical social scenes). Doing “the right thing” will always be determined by the intentionalities of all actors on the scene, through the collective intentionalities of the center, and thus doesn’t constraints or guardrails to be functional – i.e. what we call ethics. Choosing long-term pleasure over short-term pleasure is an ethic to make “pleasure” somewhat viable; choosing to not engage in violence and only trade is an ethic to make “freedom” productive; choosing to only act peacefully when mutually reciprocated is an ethic to make “peace” non-suicidal. Conversely, virtue is the sum of ethics and morality, and thus ethics is an intrinsic to virtue – why it doesn’t require an ethic to accompany it.2

The Hellenes of antiquity knew that there was something special about virtue, why we still to this day call it “virtue ethics”. And I hope the keen reader has come away with an understanding (and agreement) of why virtue works as a highest good – and I’d argue it’s the only highest good.

Why Zeno Was Right

As laid out already, only virtue would achieve eudaimonia according to Zeno – and he was exactly right. Understood as flourishing, we do so best when acting virtuously, both as individuals and as collectives. Because virtue is informed by the collective intentionality of the center on the human scene (i.e. the moral symmetry), it means acting the way people wish each other to act. And when everyone acts rightly, without shirking one’s duties or social loafing, we treat each other as we wish to be treated and our individual and collective efforts are able to achieve so much more. Obviously that is an idyllic scenario, and not everyone will be virtuous, whence the calculus changes (e.g. instead of creating something, the virtuous thing to do might be to spend time and effort on confronting those who have trouble conforming to the ethical standards or moral symmetry).

Hence virtue is only and exactly what’s needed to flourish. E.g. one could act immorally and be corrupt by privatizing public funds for oneself, and spend them on personal comforts – though it may provide oneself with some pleasure, it reduces the collective flourishing substantially. This erosion is liable to come back and affect oneself in some ways, e.g. if the embellished funds had gone to a project that’d have invented the internet, but due to the embellishment it never gets invented – one never knows which opportunity costs vicious behavior incurs (if nothing else, some amount of worry that one gets found out seems likely, which alone diminishes one’s flourishing).

When the Classical Stoics spoke of freedom, they tied it to discipline, and that disciplining yourself would free you from the volatility of passions. This is in a sense creating a disciplinary space within yourself, to abet maximum action toward virtue, and hence freedom in the Classical Stoics wasn’t tied to a rebellion against nomos. Those who have read my book will know that I contend that a modern concept that might better fit what the Stoics referring to would be that of “agency”.

One small way this view may diverge from the classical Stoics, is in how exceptional it is. Because they considered virtue exceptionally rare, with few people ever reaching it. While I don’t think this view trivializes it at all, it does make it a bit more commonly available – and I don’t see that as a problem. From my perspective, most people are actually virtuous, at least some of the time – virtue is what allows our society function, and that there in any collective or social order must be at least a minimum of virtue that binds it together (if none exists, why does it exist at all?). Even if not always virtuous, there’s still some virtue in the vast majority of people – and it’s the responsibility of the pedagogues of the human race to develop and expand upon.