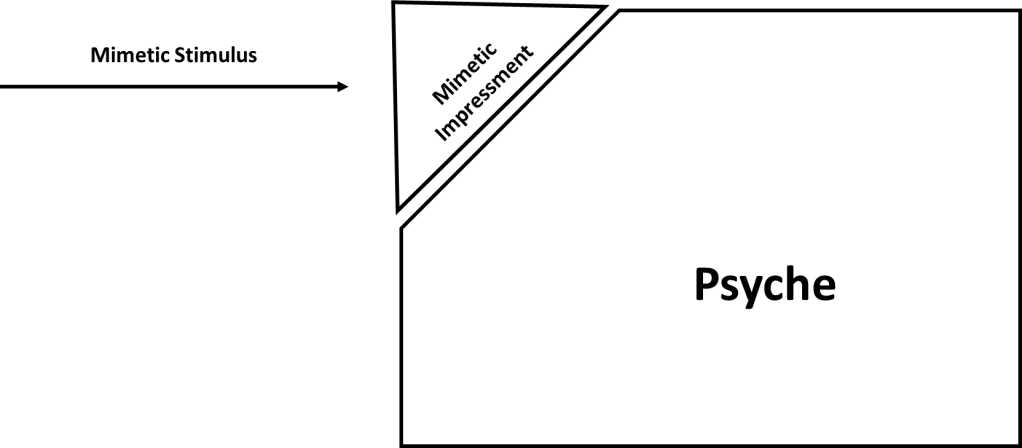

In his musings on fate, Chrysippus likened actions, attributable to man, to a cylinder. A push would get a cylinder rolling, while the same push wouldn’t move a cube to the same extent. Yet their movement isn’t merely caused by the push, but rather determined by the shape. He considered the push an “antecedent cause”, something that applied elsewhere, on another shape, wouldn’t result in the same outcome – and he judged the actions of man to be analogous to that of shapes for the reason that the exterior world gives rise to all sorts of impressions and presentations, yet people react differently to ostensibly same stimuli.

The Stoics of antiquity reasoned that the shape of our psyche, how it was physically formed (remember that the ancient Stoics considered stimulus to physically “imprint” on the psyche, why it’s called an “impression” even today) impacted the range of plausible actions one was more or less likely to take as a response to a given stimulus. Whilst the consensus today doesn’t consider our brain or mind to be physically changed by the stimuli we received, Chryssipus’ analogy is still a performative heuristic to have in mind.

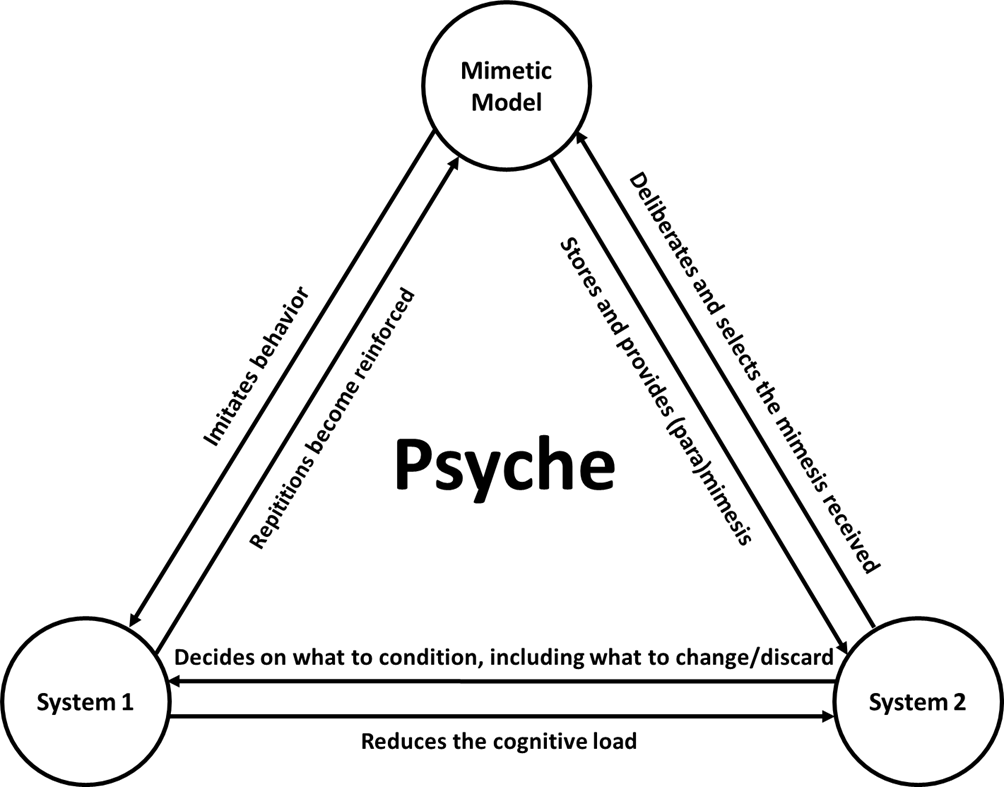

Those whom have read Daniel Kahneman’s “Thinking, Fast & Slow” will know that what Stoics call reason maps onto the “system 2” of his dual theory of mind. This is the part of our mind that enables us to act with agency; however he makes it clear that it’s a highly resource intensive system, limited in usage, and not fit for the vast majority of tasks and stimuli we face in our daily life. Rather, the vast majority of our impulses and responses to various stimuli (whether internal or external) are actually handled by what Kahneman calls “system 1”. He postulates that system 1 is a highly efficient system, running in the “background” with basically no effort; where our conscious sapience resides in system 2, system 1 is in contrast a system for all of our learnt habits, routines, muscle memories, behavioral patterns, systems, and conditioned responses – reactively shaped by all of our prior experiences and actions.

This system that gradually adapts to and internalizes one’s actions bears remarkable semblance to Chrysippus allegory of the shape of the psyche determining the likelihood of how a given stimulus is going to move one into action. For example, watching television and scrolling through social media are learnt habits in the same way that meditating or jogging is (or can be) – they’re learnt behaviors, impulses, that (may) get triggered by a certain (range of) stimulus. The vast majority aids us in getting through our day, our life, for things we shouldn’t spend a lot of mental effort on; like tying our shoes (something that took painstakingly long to develop muscle memory for, for this author). Conversely, some may progress into becoming “bad” habits, becoming a detriment achieving one’s goals or acting agentically – like eating to deal with stress or exhaustion (or scrolling through social media, resorting to various form of entertainment, or just throwing yourself on the couch).

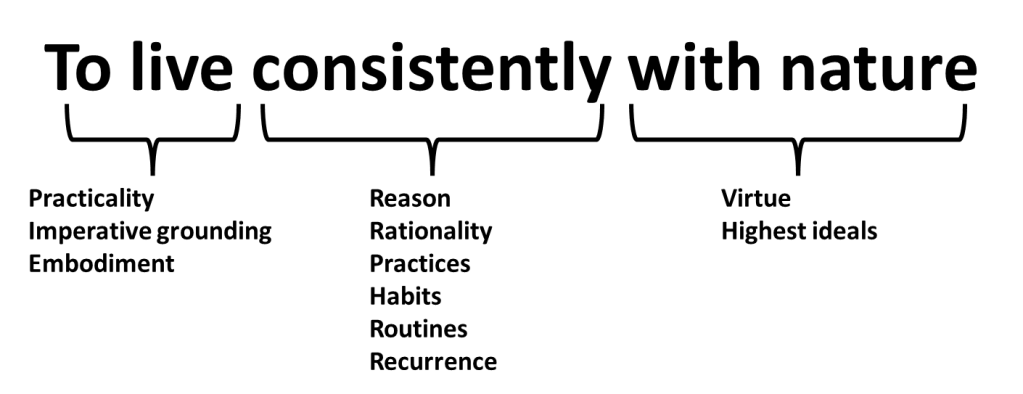

Our brain generally prefers the path of least resistance – particularly when our capacity for reason has already been drained – which is act out one’s habits, routines, and muscle memory because they require next to no effort. Hence as we grow to become an adult, everything we’ve internalized in our system 1 will increasingly come to shape our actions in most domains of our life. However, habits and routines aren’t created equal, and some require a greater system 2 effort – discipline - to internalize than others; moreover, once a habit, routine, or muscle memory has been developed, it requires even greater exertions of effort to undo because one has to both consciously avoid falling into repeating it, while simultaneously replace it with something else. This is why I in my book advocate for habits and routines to be adopted into Stoicism and elevated to the same level as “reason” itself enjoys within the philosophy. In my book I even suggest adding it as an assumption to the founding idiom itself:

Note that there’s even another resemblance with the classical Stoic belief in stimuli physically shaping the psyche, as internalizing habits and routines will develop physical neurological pathways in the brain, however that’s incidental to the performative point. As an ethos which principal aim is to perfect our service to virtue, theory, techniques, and advice must be developed and expanded upon to address this aspect of our psyche (I do so in my book, however qua the technique of ethopoetic journaling it bears revisiting). And it must be kept in mind whenever reason and rationality are being contemplated, as system 1 is a companion that can both be a hindrance but also an enabler – however one that’ll always be by system 2’s side.

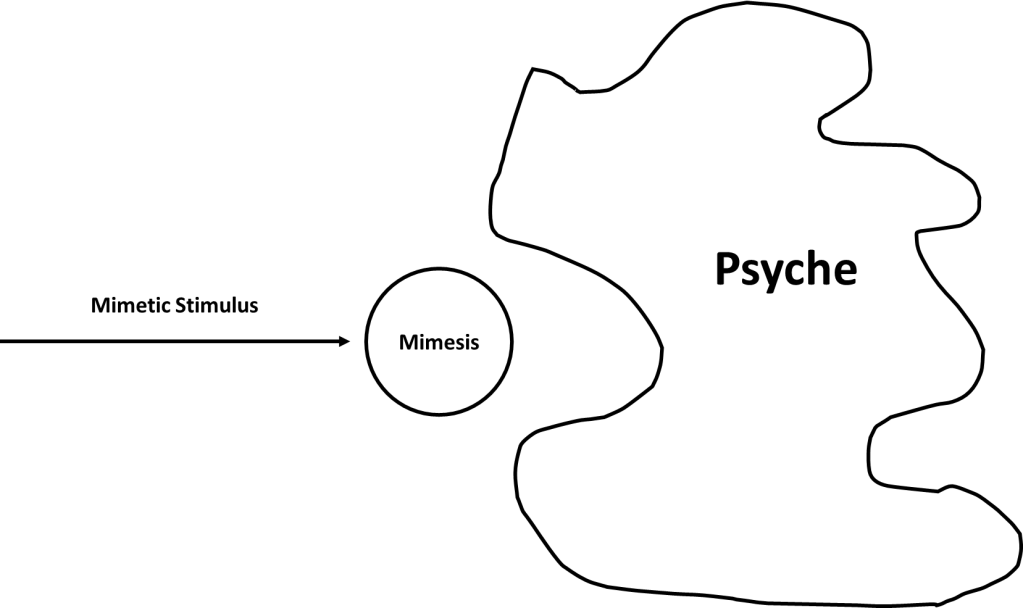

However, those already acquainted with Generative Anthropology will know that system 1 of Daniel Kahneman isn’t the only thing that shapes one’s psyche. Per the adapted (and expanded upon) mimetic theory of René Girard, human consciousness is a composite of all the mimesis and mimisms1 we’ve been exposed to throughout life, and which have taken hold. I briefly laid out Generative Anthropology’s origin of desire in my article on resentment; however René Girard contemplated human desire and concluded that to figure out what to desire we imitate the desires of others. He then goes on to formulate the “romantic lie” that’s the pervasive view of the human constitution, that our desires originate deep within our “true self” and is the most intimate expression of ourselves. Rather, Girard reasons, our desires are created through the desires, and deep-seated desires we may consider inherent to ourselves may rather originate from imitating other actors, whom we’ve perhaps forgotten we’re even imitating.

Similarly, our entire consciousness and personality is made up from mimesis, resulting in an internal “model” made of mimesis. For example, when we sit and listen to someone who’s speaking, the mimism of “sitting quietly and paying attention” will for most people, originate in an imitation of others early in life, like in kindergarten or school. This mimesis is added to, or impressed upon, the internal model and then repeated as a mimism – completely like René Girard conjectured desires to function, just scaled beyond desires to entirety of the human.

And mimesis impressing itself upon internal model corresponds to the classical Stoic view of the human psyche, sculpting it through life and gradually shaping the range and likelihood of responses and actions to various stimuli – which is why I consider this to be the human psyche proper, and was the understanding I worked with in my book (essentially saving the classical Stoic understanding in practice).

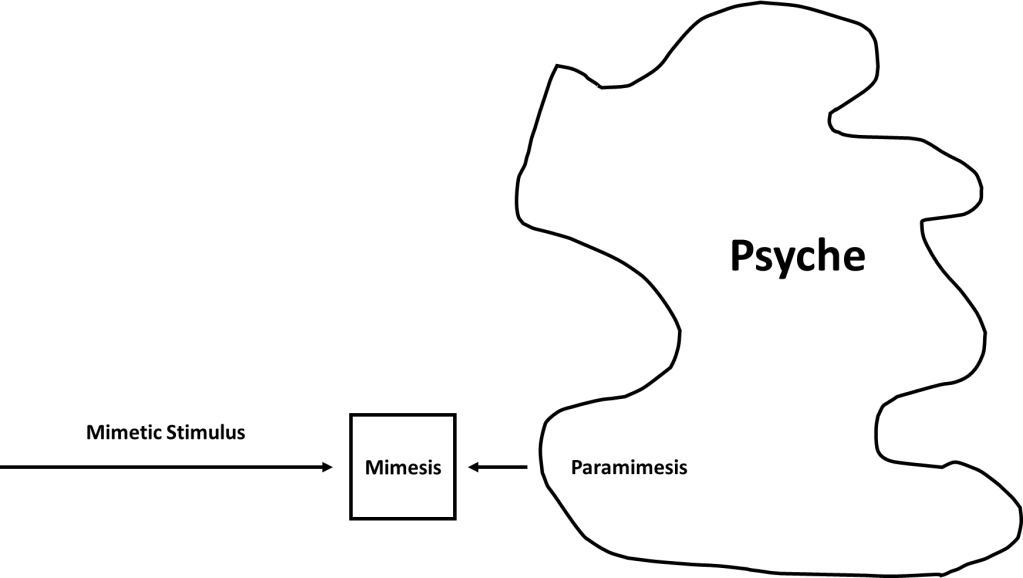

Addressing a question or issue some might have with mimetic theory, if humans are essentially mimetic all the way down, being entirely mimesis, then how come we’re not imitating each other all the time? Like in the previous example with sitting down and listening when someone is presenting, why don’t everyone stand up and mimic them? When writing my book I conceived the notion of “paramimesis” to clarify this phenomenon, because we’re very rarely imitating other people 1:1 at the same time (even if e.g. body posture and language often get imitated in active conversation). The mimesis that’s been internalized into one’s internal model acts as a “counterbalance” to the mimetic stimulus being encountered in the present moment, inhibiting it from taking hold. This is the reason our psyches differ, and why our responses to given stimuli in ostensibly the same position vary – whether the antecedent gets the ball rolling or is barely able to move it at all.

It should probably be said this mimetic aspect of the psyche doesn’t quite fit into Kahneman’s dual theory of mind, but rather is something third that invades (or interacts with) the two systems. Because mimesis that’s lodged itself into one’s mimetic model may become repeated to an extent it also finds itself into system 1, becoming an automatic habit, routine, or pattern in how you act. That could for example be how you speak and express yourself, or the body language used in various situations. And it probably also works the other way as well, where a pattern in system 1 gets mimetically imitated and then reinforced back into the mimetic model. Thus, it seems to me there’s great interplay between the two, reinforcing one another, shaping our character.

Yet mimesis, and the mimetic model, is also present in system 2. Those familiar with the originary hypothesis will know that it’s a unique degree of mimesis2 that facilitated the mimetic crisis that’d lead to the first sign being issue, inaugurating the human through the first use of abstract language. Being aware that other actors are perceiving us, just as oneself is perceiving them, results in human being able to deliberately target or manipulate the mimesis they’re exposing others to – for example enabling us to purposefully teach other people. Whether or not Kahneman’s system 2 has equivalents in other animals, or is unique to humans, is a task for dedicated researchers that I cannot feasibly answer3. However, there’s no doubt that when mimesis in the human sense enters the picture, conscious deliberation becomes exponentially more complex when having to account for how one’s mimesis may be impressing on others, and how they’ll mimetically respond back, now having to account to how your mimetic response will be to their mimetic response, to your mimetic response, to their mimetic response, to...

Those who’ve read my book will know that I identify “reason” – i.e. logos – to be a post-ritual concept that’s supposed to restore the constraints to, among other things, to passions and desires which were freed when the ritual orders transitioned to the post-ritual orders (in which the Greek city states were among the earliest, why philosophy as a discipline emerged in the first place). Reason is an imitation as well, and therefore a mimism we extract from the mimetic model of our psyche, a learned ritual that can be applied to paramimetically counteract unwelcome mimesis. That reason has been elevated to such high regards may be because it’s a mimism that’s entirely and explicitly intended for system 2, directing attention to the fact that humans can internally deliberate and manipulate mimesis; compare, evaluate, and draw upon the mimesis that’d best serve scene and center one is operating on.

Now that a contemporary version of the Stoic psyche has been laid out as this trinity of system 1, system 2, as well as the internal mimetic model, reasoned deliberation of practical measures for the self-cultivation of one’s own psyche can commence. The learned Stoic ought to find this a more performative model of the psyche, that retains the classically performative aspects whilst updating it with contemporary theories of mind that simultaneously expands upon the range of performative qualities. Note that some of the following techniques and advice were also covered in my book.

The mimetic model

Whatever we pay attention to impacts the internal mimetic model to some extent. As the model grows and develops over time, however we choose to spend our attention carries greater weight the younger we are – and those with small children can attest to the fact that they are basically small clones of their parents. When young the imitation will be nearly 1:1 with whomever is being imitated, and with time as one’s model accumulates mimesis, becomes sculpted, and more set, will imitation generally be much more subtle or extend themselves into other circumstances unrelated to situation the mimesis first presented itself. Suffice to say, it’s of vital importance that one is in control of where one’s attention is directed, as imitating anything through action has a direct impact on your character4.

Hence the first step of cultivating one’s own psyche comes from directing one’s attention toward those who have the attractive traits and character one’s looking to adopt. The ancient Stoics had a similar concept known as “prosoche”, which directly just translates to “attention”, but to the Stoics it was a practice of inwardly observing oneself; one’s sensations, emotions, thoughts, judgments, actions, etc. In contrast, this is explicitly about observing the external world and letting it imprint on you – though you can with advantage combine the two for a potent combo. Merely directing one’s attention toward someone increases the odds that they become part of oneself; however, the more one can interact the more well-rounded and immersed mimetic imprinting is possible. Suffice to say being among other people in real life, whose qualities one’s trying to take on, will have the best effect (as well as being able to influence what they’ll exhibit); whilst interacting through, or just observing via, various forms of media will have less of an effect (though still an effect, so it can be quite worthwhile still).

I personally went through such a journey myself recently, where I for a few months were immersed in a completely different environment with a lot more different people of varied backgrounds than I was used to. Armed with the advice and techniques from my book, I intentionally laid bare my psyche and were open to letting other people imprint on me – actively pursuing and encouraging it5. I made three rules for myself: 1) Be as social as possible; 2) be as active as possible; 3) engage in as many novel things as possible (novel to me). The results were spectacular, and I was able to pad out some rough edges of my psyche, making me a more well-rounded person overall. I opened myself up to the point that I was essentially a mirror for other people’s mimesis (within reason) attempting to be as receptive as a child first learning to interact with people. And I noticed how I influenced those around me, and the effect I had on them – most importantly, how to make people feel good, safe, and at home.

Of course, you broadly want to focus on those who have attractive and virtuous qualities you want to integrate and imitate yourself. However, to develop the paramimesis necessary to prevent mimesis related to unattractive or vicious behavior from taking hold, it may be necessary to expose oneself a bit to it – sort of like a vaccination. In my book, I lay out how one may temporarily need to observe or immerse oneself in social circles with unattractive mimesis, and then withdraw oneself so that can cultivate the right sort of mimetic ballast to the mimesis witnessed. If one doesn’t do so, one might eventually get exposed to something that completely blindsides you and that one’s mimetic model can’t counteract or respond against. Hence there’s an implication here that it’s wise to expose oneself to a wide pallet of mimesis to cultivate a model that’s able to balance any and all impressions it receives – so that ball or cylinder never starts rolling without having given assent to do so. Furthermore, as one gradually cultivates the right kind of ballast, one may challenge oneself and intentionally subject oneself to prolonged exposure, increasing in length to the point of remaining entirely unfazed.

The above has implications on how one ought to raise one’s children, to cultivate a healthy and virtuous psyche within them. However, how about oneself who’s inevitably been raised much more haphazardly and exposed to-, and imprinted on, things that weren’t the most advantageous? Few are going to have been raised to be a sage from birth and thus the mimetic layers making up one’s internal model are going to be more disorganized and contorted. In this case it may be even more important to expose oneself to mimesis that can counterbalance imprints that are expressing themselves as unattractive qualities of your character. For example, locating people who have had some of the same issues as you, and then imitating the ways they overcame them may be one way; or joining social circles who exhibit the qualities that one currently lacks is another way. The important part is to do something about it, and remember that under the surface, most people are various degrees of messy – and that the layers of mimesis one is interacting with only has a straight throughline due to the intentional action to cultivate that aspect of themselves (e.g. acting “professionally”).

In my book, I equated excess idle attention to that of consuming too many calories. When consuming too many calories the body starts overproducing various hormones and cells to an overall detrimental effect for the body; and similarly when we have spare attention in excess throughout our day, it’s all too easy to direct them toward activities or screens that at best don’t provide anything of value, and at worst affects you and imprints on you negatively. Therefore, the Stoic ought to be diligent about how he constructs his daily routines and activities, seeking to minimize time throughout the day not engaged in some constructive way. This issue is especially salient at this point in time with the omnipresence of mass media, that are all designed to grab hold of your attention and keep it for as long as it can – and attention has become such a scarce resource that the term “attention economy” has been coined.

Because mimesis is obtained from others, the implication is that one must be around other people to shape one’s internal mimetic model. In my book I talk about the mutual reinforcement of virtue, because there are very few sages in the world, and only hanging out with them is way too restrictive to be practical (practicality being a central aspect of Stoicism, per the founding idiom). Rather, it’s advantageous for the Stoic to view friendship in a mimetic way, with the goodness of other people – those whom we choose to surround ourselves with – reflects our own capacity for virtue. Simply put, the Stoic ought to pursue friendships with people who’ll support them in their pursuit of virtue, and bring out the best in them – and the Stoic will in turn support these people and bring out the best in them. Stoic relationships – whether friendships, romantic, or otherwise – ought to ideally be based on mutual growth towards virtue; conversely, relationships that are “toxic” and bring out the worst in each other, dragging one another down, ought to be rejected and avoided.

System 1

Ever since I read Daniel Khaneman’s book Thinking, Fast & Slow I sought to “load” as much of my daily doings into system 1. I attempted to design various habits, routines, muscle memory, patterns, systems, and conditioning of myself – for example, I always do fitness straight after my regular daily commitments are finished (e.g. schooling or work) and always on the same days; that doesn’t mean that sometimes things won’t get switched around for various reasons, but I’m committed to sticking to the routine within reason. And things I have with me regularly always go in the same pocket, so I don’t even have to consider where things are. I did this during my studies so that I had some extra mental capacity I could use for studying – and now for self-studying and producing intellectual work.

And that seems to me the mindset the Stoic ought to have towards system 1. While it may be discomforting to consider that our capacity for reason is limited and must be rationed, it should be a reassurance that there’s a complementary system that we can condition to supplement our reason. In a sense, the Stoic should actively be trying to commit as many things as they can to system 1, so that a greater portion of their limited reason can be committed towards higher endeavors, instead being forced utilizing it on mediocre tasks by necessity. For example, when first learning to cook food one must commit one’s system 2 to learning how do the various culinary techniques and follow the recipes, however over time these things become learnt and committed to system 1; so even though the Stoic may be engaged in an activity like cooking that does take some effort, the more has been internalized in system 1, the fewer resources are needed from system 2 - and can perhaps be spent simultaneously mulling over higher endeavors (why it’s so important that e.g. things always are placed in the same spot, so system 1 can just automatically go through the motions and not get pulled out of it when things are missing to go find it).

As just suggested, the Stoic ought to take time – ideally early on – in their life to utilize their reason to commit as many things into their system 1 that they can, so that they later on maximize their system 2 capacity that can be spent on higher endeavors. While in the short run it’ll take some focus away, it’ll yield dividends in the long run6 – for the rest of one’s life. But what should one commit? Returning to the founding idiom of Stoicism, the Stoic ultimately always strives towards virtue – meaning that whatever’s internalized into system 1 should in some way, shape, or form abet their dedication to being virtuous. While cooking food is ostensibly an indifferent, it’s a task that the Stoic will undoubtedly need to simply live, and hence getting so good at it that it becomes mentally effortless (and likely less time consuming) will indirectly have the effect that more capacity (and time) can be committed towards the higher aspirations of virtue.

As mentioned, the Stoic should be prospicient for how they best serve virtue in the long run – e.g. practicing sport or fitness helps prevent one’s body (and mind) from deteriorating as one ages, keeping oneself fit in the service of virtue longer. But things like reading, studying, working, building, creating, and of course, practicing virtue, are all in some sense habits, routines, or systems that can be formed. As previously mentioned, entertainment like television or social media are themselves forms of habits – just ones that are designed to be easy to acquire. However the greater effort a habit requires to internalize, the greater its value will tend to be; and when they’re formed, they’ll make the corresponding tasks that much more effortless. Obtaining good habits at a young age won’t just yield dividends over a longer period, it’s also much easier the younger one is (due to greater neural plasticity and relatively fewer responsibilities) – why it’s so important. as a parent. that you have your children read books instead of sitting them in front of a tablet.

A minor drawback that I’ve experienced from committing as much as I can to system 1, is when things aren’t normal, as implied earlier. I generally tend to leave myself some wiggle room for my larger and more important routines, so that I can move things around and still make everything most of the time. However, on the smaller daily tasks that have been internalized so completely that I barely process they are happening, that’s where I’ll sometimes have issues – when things are out of order. Like the cooking example earlier, the more completely my internalization, the greater my confusion and bewilderment when I get taken out of it becomes things aren’t where they’re supposed to be (in the sequence), and the automatic process of system 1 has been halted. That’s why when one does this, one must ensure to be orderly and keep a tight structure (especially when living together with a partner) – greater orderliness enables greater system 1 automation. Likewise, when one must undo a habit or routine for a new one (or just adjust an existing one), the more it’s internalized the more it takes; and I’ve frequently just completely forgotten that I was supposed to be doing something else, whence I have to backtrack to start over with the new routine (and I recommend starting over, so you’re not activating and reinforcing the old routine) – suffice to say, the more you’ve committed into system 1, the more often you’ll encounter having to adjust or change something internalized, which does require some extra efforts. I imagine especially towards the beginning, there’ll be some missteps in what’s internalized, until one becomes more acquainted with system 1 internalization as a whole, and can better assess how internalize the right things in the right way, that’ll last as long as possible.

System 2

Where doing difficult things to internalize them in system 1 eases them because the psyche knows how to execute them blindfolded, doing difficult things in the present trivializes doing difficult things in the future by strengthening system 2. As I write about in my book, this system is comparable to a muscle – and using and stressing it makes it grow. Given reason’s central importance to the Stoics, going all the way back to antiquity, it’s imperative that the Stoic expands his capacity to this greatest extent feasible. And, similarly to a muscle, there’s two ways to go about it: 1) Engage in evermore intensely demanding mental task; 2) sustain one’s focused attention for as long as possible. Keeping with the comparison to a muscle, the first is the raw strength, how much your system 2 and reason can handle at once – and the greater the volume of stimuli, knowledge, mimesis, etc. one can process at any given time, the greater the odds that one’ll act within right reason, i.e. virtuously. The second is one’s endurance, how long one can keep utilizing one’s system 2 and reason without needing to recuperate.

Needless to say, this is why the Stoic must keep exercising their mental faculties – because like a muscle, if one stops exercising it, it’ll atrophy. And this is a word of caution, because even though one may think one is engaging in cognitively demanding tasks on a regular basis, if they’re the same kind of tasks, they’ll gradually become internalized into system 1 – and thus not exercising system 2 anymore. I’ve personally observed how otherwise intellectually accomplished people become broken records with age, and their unwillingness to reconcile or recognize new ideas or developments that may challenge their work7. Hence despite how much the Stoic has exercised their system 2 in the past, it’s essential to keep maintaining regardless, pursuing new vectors of challenge. Otherwise their contributions may overtime fade from virtuous to inconsequential at best, and vicious at worst.

And system 2 has some big responsibilities that it deserves the best conditions for. Because this is the part that can actively deliberate, make choices, be proactive, and regulate what’s going into the other two parts of the psyche – like a computer program that’s able actively decide to write or rewrite parts of its own programming. The implication of this is that passion can only be a consequence of system 2, as the other two systems are essentially reactive – just like the ancient Stoics concluded that passion wasn’t a separate or opposing force to reason, but were different states of the same thing (which is mimesis, as it’s what allows joint attention in the first place, but is likewise liable to make your lose your attention and direct it elsewhere). Because system 1 just executes what’s been conditioned into it – its “programming” – it’s a failure of system 2 if it executes things that are an obstacle to the goals of system (“bad programming”). And the mimetic model just absorbs whatever it’s being exposed to from other actors, hence it’s up to system 2 to pay attention to the right things.

As talked about at length already, the responsibility that system 2 has toward system 1 is to condition the right things into it, so that it in turn can do itself a favor and lessen the burden upon itself. And just as important as conditioning the right things into system 1 on the first try, is its ability to evaluate existing habits, routines, patterns, systems, and conditioning and adjust or discard them for new ones, as necessary. Because one’s rarely going to internalize the right things into system 1 initially, likewise being a skill that one must learn and perfect. Even habits and routines that were a perfect fit earlier in life may have gradually become suboptimal due to change in circumstances, and thus need recalibration. As mentioned earlier, adjusting, and particularly replacing, an existing habit or routine requires extra effort to just conditioning a new one in the first place, which is why it pays off for system 2 to have extra capacity.

And the responsibility that system 2 has toward the mimetic model is to, in essence, cultivate and sculpt it in the right fashion – like a bonsai tree. As has been mentioned ad nauseum at this point, directing it toward the right things, the right people, is necessary to let the right impressions become part of the model. Because where system 1 is about minimizing the things that system 2 must manage, the mimetic model is the part of the psyche that actually provides the things that system 2 has to play around with. And if the mimetic model has absorbed mimesis that’s unattractive, it’s on system 2 to take the reigns and hold the ball (or cylinder) back from rolling – coming full circle to Chrysippus’ metaphor – and failure to do so is what results in passion. While other things – mimesis principally, but also other things like instincts and system 1 – may inform system 2, because reason itself is a machination of mimesis, it must always be the one rolling and steering the ball.

Note that the term “mimism” originates with Marcel Jousse.

Unique in the animal kingdom, as human are the only species that possess “3rd order attentionality”, whilst all other species only possess 1st or 2nd order attentionality.

My intuition is that animals do have similar systems for deliberation, that they aren’t merely instinctual and reactive, even if greatly smaller capacity than humans and unable to account for mimesis.

Recall that in my book, your character is how you act, which can be expressed through the idiom “Facio ergo sum” or “I do, therefore I am”.

I was also experimenting with other aspects of Stoicism and Generative Anthropology.

The usage of “short run” and “long run” is in the same sense as within the discipline of economics.

Obviously there’s also an aspect of sunk costs here, trying to defend their contributions – however I’ve definitely witnessed some who’s let the part of their psyche, where learning and reason resides, atrophy and are thus unable absorb new developments despite them still (ostensibly) writing and contributing intellectually.